The /r/DailyProgrammer challenge last Monday involved finding successive terms of a series, defined by a recurrence relation, given the first term of the series. The nice thing about writing these challenges is seeing the different types of solutions that people come up with. As it is a fairly simple challenge, most people opted to just repeatedly apply a function over and over to generate new terms of the series. Someone also created a JIT compiler for the recurrence relation, which I really did not expect.

As I was aware that the second part of this challenge was going to be extending this problem to solve more complex recurrence relations, I created a somewhat over-developed solution to solve both parts of the challenge at once. It’s written in F#, a nice language that I’ve recently been playing with, that is quite accessible to me due to its basis on the .NET Framework. Having used C# before, the jump from one language to another wasn’t so harsh.

When the time rolled around to submit the second half of the challenge, however, I was not on a Windows machine. F# (and Mono in general, as I have found) are a bit painful to work with if you’re not on Windows. I had already essentially solved the challenge, so I didn’t feel like starting from scratch; therefore I opted to do something I had been putting off for a while - to learn Haskell. It’s a functional language similar to F# in style and syntax, and as learning a new language is a new year’s resolution of mine, I decided to bite the bullet and re-write the solution in Haskell, learning the language as I go along.

The original F# solution used a seq to lazily generate the sequence as needed, using Seq.unfold to create a sequence with a state storing the known terms in the series. Haskell is a lazily-evaluated language, however, meaning the sequence can be represented as a list without causing an infinite recursion. To store the recurrence relation (aka successor) itself, I’m using a custom data type which stores a tree of operations to perform:

data Successor = Literal Double

| Previous Int

| Binary (Double -> Double -> Double) Successor Successor

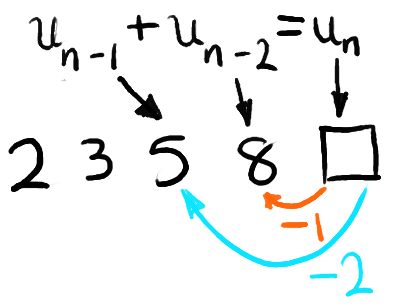

| Unary (Double -> Double) SuccessorAs you can see, binary and unary arithmetic operations are supported, as well as literals. The Previous node type is for referring to a previous term in the series, such as (Previous -1) and (Previous -2) for the last two values in the Fibonacci sequence.

Hence, the Successor representing the Fibonacci sequence would be something like this:

fibSuccessor = Binary (+) (Previous -1) (Previous -2)My solution traverses the successor tree to find the list of terms that the defined term is dependent on ([-1, -2] in this case), by looking at the Previous nodes. Then, by taking this list, you can step along the unknown terms in the series, find out whether both dependent terms are known, and then calculate those terms and add them to the known terms in the series. By doing this iteratively, you can start from a small number of known terms in the series (such as [0, 1] in the Fibonacci sequence) and build up from there.

Implementing the solution in Haskell wasn’t too bad, even having never touched it before. The Hackage documentation is very comprehensive, and most map/reduce functions are the same across all languages, so it wasn’t hard to get something up and running quickly. The ability to search by type signature was also useful.

haskell

It helped me greatly that F# and Haskell are both somewhat similar. Despite both being from different families of languages (F# having descended from ML), I solved the challenge almost identically in both. F# does have a more imperative touch to it, however - the |> (forward arrow) operator is well used by F# code - for example, the visual flow of data generally goes from left to right (or from top to bottom, if split over multiple lines), like this:

let someValue = originalData

|> List.ofArray

|> List.map exp

|> List.distinct

|> List.fold (+) 0In Haskell, however, the flow of data is reversed. Composition is mainly done with the $ operator (equivalent to <| in F#), like this:

let someValue = foldl (+) 0

$ nub

$ map exp

$ originalDataBoth examples represent chained function application, and out of the two languages, Haskell’s preferred representation is the closest to what is actually happening:

let someValue = foldl (+) 0 (nub (map exp (originalData)))In this way, I suppose F#’s |> operator reverses the application of functions by putting the argument first, even through this is what makes more intuitive sense (especially coming from an imperative language, where operations are specified sequentially). Either way, if you’re coming from F# to Haskell and you want to make it seem that little bit more comfortable, you can always re-define the |> operator and use it as you normally would.

let a |> b = b aIf you want to see my solution to the challenge, there’s the Haskell version and the F# version - the only difference being that the F# solution doesn’t accept the RPN input for Part 2 of the challenge. The use of ++ in getSeries is a little bit nasty, but I only found out that it runs in O(n) time after writing the solution.